Mary Oliver's poem "When Death Comes" unfolds as a deeply introspective meditation on mortality, existence, and the imprint one leaves behind. Oliver’s lyrical engagement with nature and introspection is a hallmark of her work, and this poem is no departure. The poem begins with the speaker acknowledging the inevitability of death. Oliver expresses a willingness to face death directly, without denial or fear. The phrase "When death comes" immediately sets a tone of acceptance and inevitability. The line “and I think of each life as a flower, as common / as a field daisy, and as singular,” captures my particular admiration. In this comparison, Oliver distills the essence of human life into the imagery of a flower, highlighting its fleeting and delicate nature. The "field daisy" emerges as a symbol of life’s ubiquity and simplicity, suggesting that while each individual life possesses its unique qualities, there remains a universal thread that links all human experiences. The contrast between "common" and "singular" reveals the inherent tension in our existence: we are at once part of a shared human condition and marked by our distinct individual narrative. The speaker's wish is not to leave behind grand achievements but rather to have lived in a way that is true to herself.

Throughout my life, I have traversed the landscape of four significant familial losses. The first was my uncle, whose memory is a distant echo from my early childhood, yet one detail stands out with striking clarity: the large teddy bear he kept in his car for me. This small, seemingly inconsequential gesture has become a poignant symbol, a fragment of affection that remains vividly alive in my recollections.

The second significant loss was my grandmother, who succumbed to the effects of a stroke at the age of 65. Despite spending considerable time with her during my childhood, I only knew her in the context of her post-stroke condition, leaving a gap where her pre-illness personality might have been.

The third loss was my grandfather, who succumbed to old age, exacerbated by the respiratory issues resulting from his years of heavy smoking. I was still a pre-teen when the swift and inexorable disintegration of his health began, and the experience was nothing short of disorienting.

The most recent loss in my life occurred in 2018 when my aunt passed away, and it was the hardest of all. Our bond had been one of the closest and most enduring in my life, making her absence deeply unsettling. Even after five years, her absence remains a palpable void. I continue to grieve and find myself frequently reflecting on her presence, struggling to reconcile the space she once filled with the reality of her absence.

As a child, weekends were often spent at the cemetery with my mom and aunt, visiting the resting places of my uncle, grandma and grandpa. We would select flowers from the grocery store, their vivid colors a stark contrast to the somber stones that awaited them. I would sit quietly, observing my mom and aunt as they prayed in silence, while my attention drifted to the delicate sound of wind chimes swaying in the breeze from nearby trees. Their melody seemed to blend with the quiet reverence of the cemetery.

When my aunt passed away, the visits to her grave became less frequent, constrained by the distance between New York and our old routines. My mom and I would make the journey together only a few times, and now, with my mom’s declining health, I find myself going to the cemetery alone. These visits are no longer a shared ritual but a solitary journey. As I stand by the stones of my uncle, grandma, grandpa, and aunt, I still lay flowers and pay my respects, but now my silent prayers accompany the familiar sound of the wind chimes, a haunting reminder of those who have gone and the continuity of memory and connection.

Death, with all its complexities, remains a profound mystery to me—both unsettling and oddly fascinating. There are days when it seems almost surreal to think that one day, both myself and everyone I know will cease to exist. For some, this contemplation may offer a strange comfort or evoke a deep discomfort. As I grapple with these thoughts, I find myself in a state of uncertain reflection.

Three months after my aunt passed away, I received a phone call from her cell that left me feeling both intrigued and frightened. I hesitated to answer, overwhelmed by confusion. I asked my uncle if he had used her phone to call me, but he hadn’t. This mysterious call still occupies my thoughts, and I often wonder what might have happened if I had answered. If she were to call again, would I have the courage to pick up?

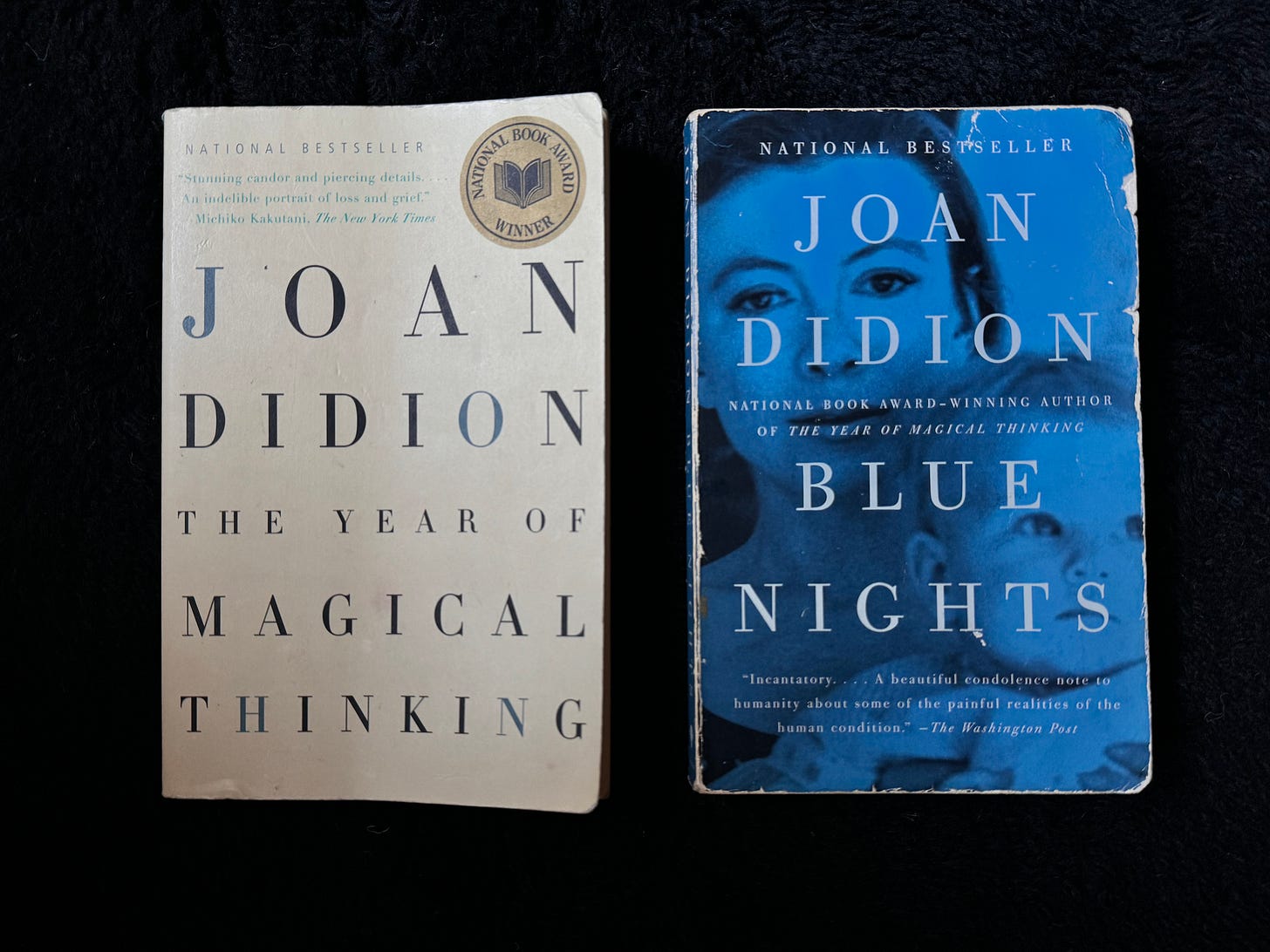

Like countless young women immersed in Tumblr between 2013 and 2016, I was enchanted by Joan Didion and her evocative prose. I first read The Year of Magical Thinking in 2014, during my fleeting thirty-minute lunch breaks at Madewell. I remember those days with a sense of wistfulness; at twenty years old, I took a (perhaps pretentious) certain pride in reading a book rather than scrolling on Instagram through my iPhone 5. The Year of Magical Thinking is Didion's memoir that explores the themes of grief, loss, and mourning following the death of her husband, John Gregory Dunne. The concept of "magical thinking" describes Didion’s emotional response to her husband’s passing, characterized by her irrational hope that clinging to his belongings and routines might somehow reverse or delay the harsh reality of his death. This term vividly captures the struggle to come to terms with an incomprehensible loss.

A year later, I picked up Didion’s Blue Nights, and although I initially doubted that anything could surpass The Year of Magical Thinking, Blue Nights proved me wrong. The book focuses on the aftermath of her daughter Quintana Roo Dunne’s death in 2005, examining the deep impact this loss had on Didion’s life. It delves into themes of aging and the inherent fragility of life. She thoughtfully considers her relationship with her daughter and how memories and personal histories are constructed and preserved. The memoir also addresses the concept of legacy—what we leave behind and how our lives are perceived and remembered by others.

Joan Didion’s writing is so iconic that I imagine anyone reading this is already well-acquainted with her work. For me, those two books were among the first I discovered as a young adult, and they hold a special place in my memory. They marked my initial foray into literature about grief and death, leaving a lasting impact on my understanding of these themes.

Flowers, with their brief and bloom, embody the transient nature of our existence. They emerge in a burst of color and vitality, only to wither and fade with the passage of time. This fleeting cycle reflects the impermanence of our own lives, serving as a poignant reminder of how quickly and irreversibly moments can slip away

In the realm of ancient Greek mythology, the narcissus flower emerges as an emblem of both ephemeral beauty and and its inevitable end. The myth of Narcissus, whose profound infatuation with his own reflection led to his demise, intertwines with the flower in a tale of vanity, mortality, and metamorphosis. As Narcissus lingered, entranced by his image until his last breath, the ground where he perished gave rise to the narcissus bloom—a delicate yet haunting testament to the fragile dance between life and death.

In Victorian England, the practice of “floriography”, or the language of flowers, was a delicate art used to convey feelings that were too difficult to voice openly. Each flower was chosen for its symbolic meaning, and this careful selection was especially poignant during funerals. Lilies, for instance, have long been associated with purity and the soul’s return to a state of innocence after death. Particularly, white lilies are commonly used in funerals to symbolize the restored innocence of the deceased. In Japan, these flowers carried a solemn significance, woven into funeral arrangements to express deep sorrow. Meanwhile, in Europe, they were gently placed on graves during All Soul’s Day, a quiet tradition of honoring and remembering those who had passed.

The scent of flowers at funerals carries a dual purpose, woven into the fabric of tradition and necessity. Historically, before the development of modern embalming techniques, the scent of flowers was used to mask the odor of decay. Even as the flowers withered, their lingering aroma—akin to the enduring memories of the deceased—provided a subtle yet profound comfort, maintaining a sense of connection that transcended their physical presence.

The practice of visiting graves has ancient origins, with evidence suggesting that early humans engaged in similar rituals. Archaeological findings from the Stone Age reveal that flowers and other offerings were placed in graves, indicating a belief in the importance of providing for the deceased in the afterlife. This early practice reflects a sense of respect and care for the dead, suggesting that grave visitation was not only about honoring the deceased but also about ensuring their comfort and well-being beyond life.

As we move into medieval Europe, this practice acquires a distinctly religious dimension. Here, grave visitation is woven into the fabric of Christian ritual, an act imbued with the weight of spiritual necessity. To visit a grave and offer prayers was not merely an expression of grief but a vital intervention on behalf of souls navigating the uncertain waters of purgatory. The formality with which these visits are conducted reflects a broader attempt to merge personal loss with an overarching framework of spiritual belief, making the act of remembrance a profoundly ritualistic endeavor.

Love,

Iris

Film and television mentioned in order:

Nathan For You (2013-2017)

Broken Flowers (2005) Dir. Jim Jarmusch

The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) Dir. Wes Anderson

Steel Magnolias (1989) Dir. Herbert Ross

All About My Mother (1999) Dir. Pedro Almodóvar

Hereditary (2018) Dir. Ari Aster

Up (2009) Dir. Pete Docter

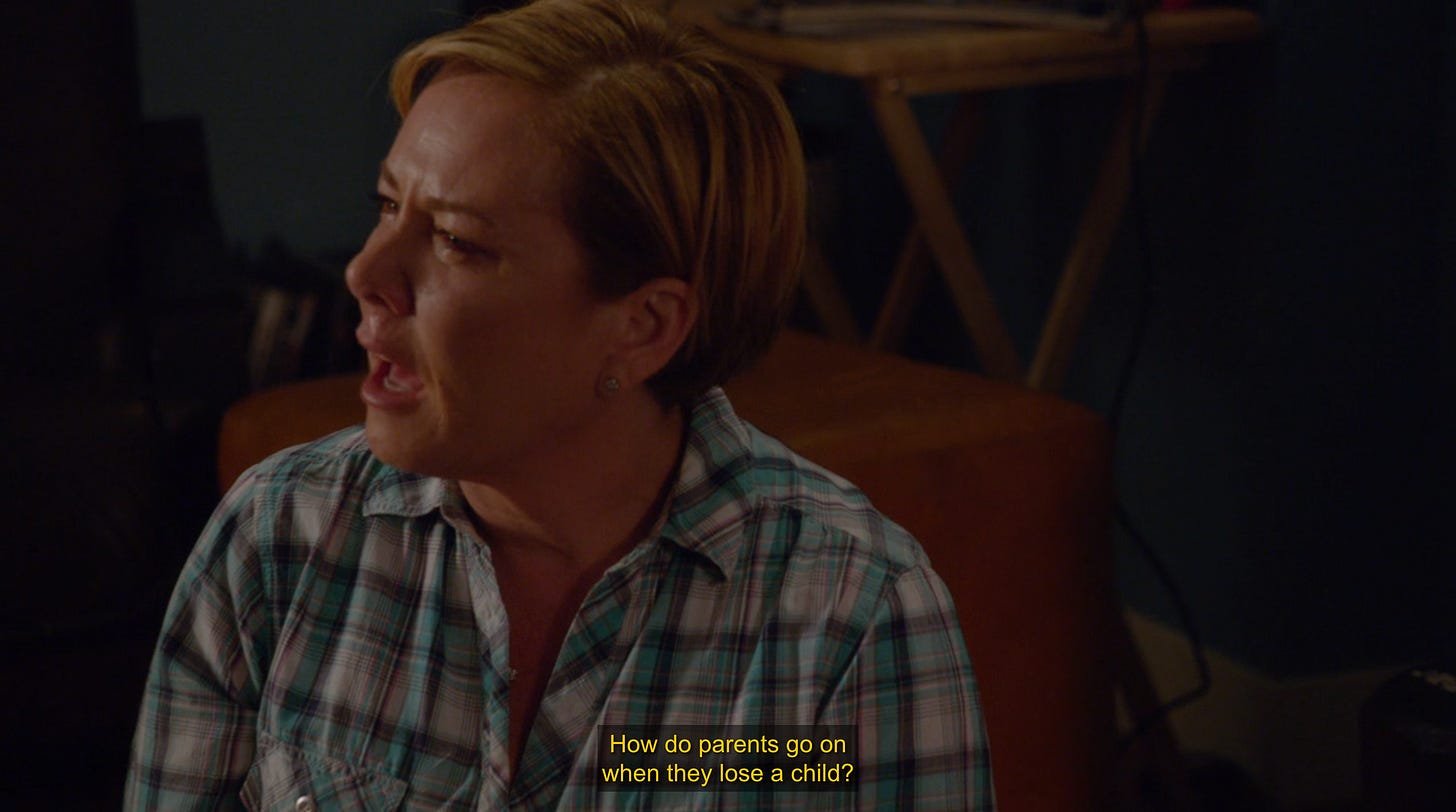

Glee (2009-2015)

French Postcard (1979) Dir. Willard Huyck

The Perfume of the Lady in Black (1974) Dir. Francesco Barilli

The Strangler of Blackmoor Castle (1963) Dir. Harald Reinl

Secret Ceremony (1968) Dir. Joseph Losey

Death Becomes Her (1992) Dir. Robert Zemeckis

Pet Sematary (1989) Dir. Mary Lambert

Ringing Bell (1978) Dir. Masami Hata

Videodrome (1983) Dir. David Cronenberg

Heathers (1988) Dir. Michael Lehmann

El Norte (1983) Dir. Gregory Nava

The Lion King (1994) Dir. Rob Minkoff, Roger Allers

Firepower (1979) Dir. Michael Winner

The Tomb of Ligeia (1964) Dir. Roger Corman

The Virgin Suicides (1999) Dir. Sofia Coppola

The Host (2006) Dir. Bong Joon-ho

Succession (2018-2023)

Memories (1995) Dir. Katsuhiro Otomo, Koji Morimoto, Tensai Okamura

Little Miss Sunshine (2006) Dir. Valerie Faris, Jonathan Dayton

Don’t Look Now (1973) Dir. Nicolas Roeg

I love this exploration of death—it’s something we don’t talk about enough—through flowers in films. 💐 So many of these I need to rewatch, and El Norte is now on my list. I’m not familiar with it, but it looks beautifully filmed from the screenshot you shared. 🎥 I hope your aunt calls back. 📱❤️